This piece takes a clear look at a specific media claim and its accuracy, examines how political rhetoric has been used by opponents, and explains why the claim matters for public trust and political debate. It argues from a Republican perspective that the error is not minor, traces how comparisons to historical tyrants entered public conversation, and points out consequences for fair coverage. The goal is to hold the record straight while staying focused on facts and observable patterns.

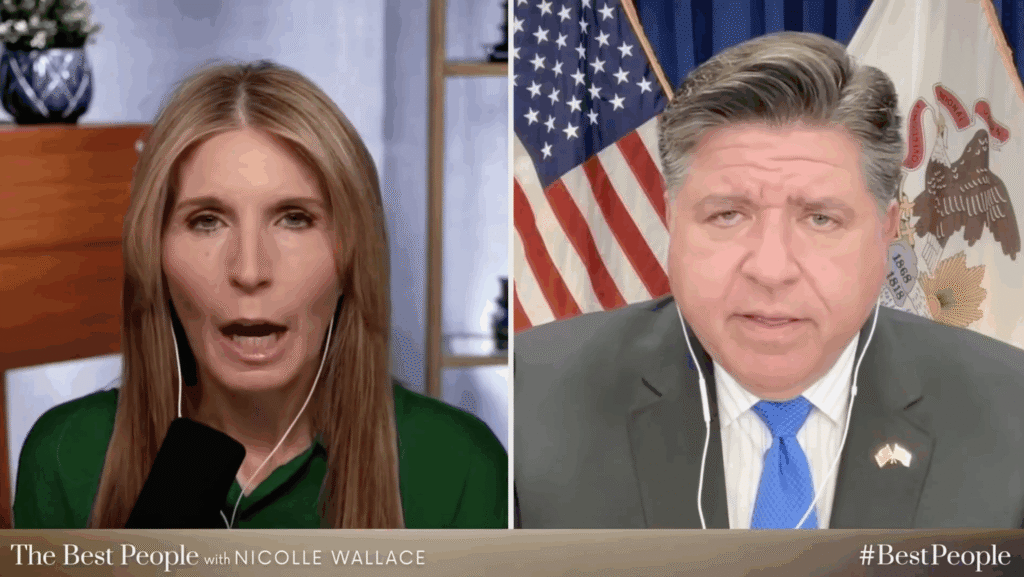

“Wallace’s claim that no Democrat has ever suggested Trump is Hitler is demonstrably false.” That sentence captures the core dispute, and it deserves scrutiny rather than a shrug. Getting that basic factual point wrong matters because it shapes how viewers evaluate commentators and networks.

Across the last several years, voices on the left used Hitler and fascism as shorthand for extreme danger, often invoking those comparisons in protests, columns, and television segments. Those comparisons were not always framed as measured historical analysis, they were blunt rhetorical attacks designed to mobilize and alarm. The pattern was visible and repeated enough that it left a clear public record of the rhetorical choices on one side of the spectrum.

Accusing someone of being Hitler is not a neutral claim, it is the ultimate moral condemnation and it carries heavy historical weight. For Republicans, the problem is twofold: first, the accusation was frequently overheated and lacking in careful evidence, and second, when mainstream journalists deny the existence of such comparisons, it looks like a refusal to acknowledge an obvious pattern. That combination erodes trust in media institutions tasked with fair reporting.

There are legitimate ways to critique political leaders without invoking the worst regimes in history, and responsible debate benefits when such language is avoided. Conservative voters and commentators rightly push back when their opponents deploy hyperbole that blocks real policy discussion. Calling out exaggerated rhetoric is about restoring a sense of proportionality to political argument, not about defending every action of a public official.

When a respected broadcaster declares that no Democrat ever made a particular comparison, listeners expect that statement to reflect the record. Mistakes like that are not just trivia, they affect how the audience judges the outlet’s accuracy and bias. From a Republican view, insisting on factual accuracy is essential, especially when the error favors one side by erasing its own more extreme language.

Critics on the left will say that such comparisons were symbolic, rhetorical flourishes meant to warn rather than to accuse in a literal sense. Yet rhetorical context matters, and so does pattern. Repeated use of dehumanizing or totalitarian labels creates a public impression that crosses from argument into character assassination. That shift diminishes the quality of political life and helps no one who cares about civil discourse.

This is also about precedent. If public figures and media personalities keep denying obvious patterns because those patterns reflect poorly on their side, readers and viewers lose faith in neutral reporting. Republicans argue that holding all sides to consistent standards of accuracy is essential for a functioning public square. Pointing out a misstatement is an attempt to enforce that standard, not to score cheap partisan points.

Finally, acknowledging what actually happened does not grant moral equivalence between political actors, it simply recognizes reality so voters can make informed choices. The issue here is accountability for words and for claims about what did or did not occur. Making that distinction is part of rebuilding a media environment where assertions can be checked and corrected without partisan excuses.