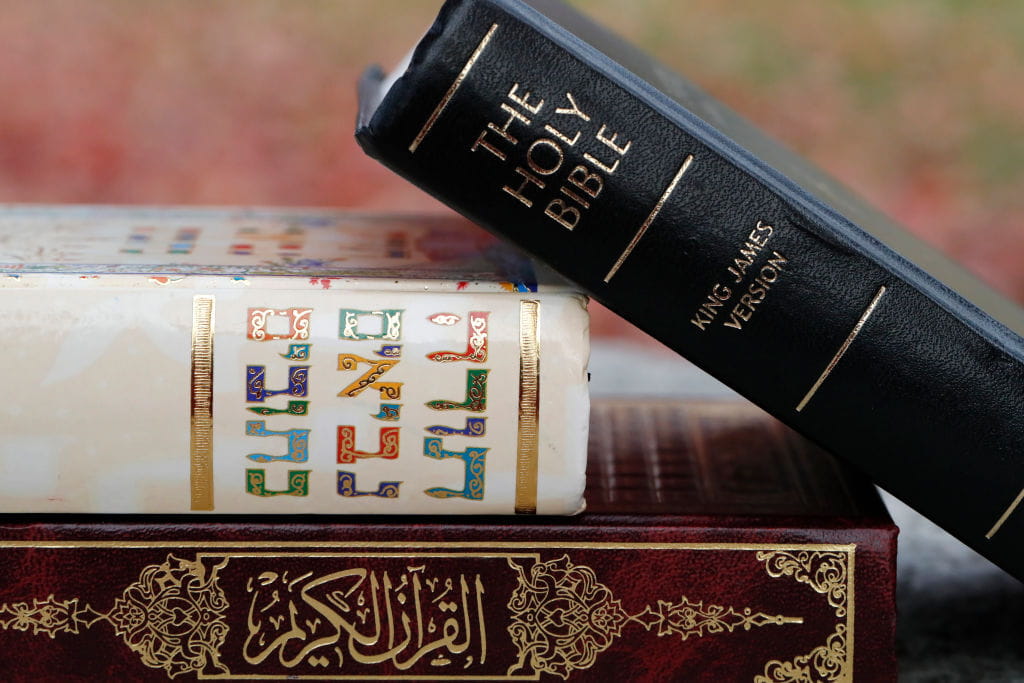

MyCross’s new study finds a striking gap between offline numbers and online presence: Christianity remains the world’s largest religion by followers, yet Islam has taken the lead across the internet, raising questions about how digital reach and real-world demographics interact.

Christianity has been the largest religion in the world for centuries, and that remains true in headcount according to recent reporting. The MyCross study points out that Christians still greatly outnumbered Muslims in 2025, a fact that anchors the conversation in demographic reality. At the same time, the same research notes a very different picture online, where Islam dominated the internet in visibility and engagement.

The gap between population totals and online influence matters because the internet shapes ideas fast and broadly. Islamic pages, videos, and social accounts drew disproportionate attention, giving Islam more digital momentum even without overtaking Christianity by followers. That digital strength can shift perceptions, conversations, and conversions in ways that raw population numbers do not immediately reflect.

Observers have suggested a few reasons for the online tilt toward Islam, including active content creation, savvy use of video platforms, and strong community networks on social apps. Younger demographics in many Muslim-majority countries are intensely online, producing a steady stream of shareable content and local voices. Those patterns combine into an ecosystem where content spreads quickly, sometimes faster than traditional institutions can respond.

Platform algorithms also play a role by elevating content that sparks engagement, and religious material often meets that test when it is emotive or controversial. Viral formats such as short clips, debates, and personal testimonies tend to amplify messages regardless of their origin. As a result, Islam’s digital footprint can look larger than its offline numbers imply, especially on platforms where visuals and rapid interaction dominate.

That divergence prompts the provocative question posed in the original reporting: “Does this trend foreshadow a future in which Muhammad claims more followers than Jesus, or is […]” The sentence hangs in the report the same way it does here, signaling uncertainty about whether online dominance will translate to broader demographic change. It’s a question worth attention because it ties online cultural influence to potential long-term shifts in religious affiliation.

Demographics still matter. Birth rates, conversion trends, migration, and generational identity shape religious make-up over decades, and those forces do not flip overnight because of trending hashtags or popular videos. Yet history shows cultural shifts can accelerate when new communication technologies change who talks to whom and how beliefs are shared, taught, and reinforced across borders.

Religious communities respond differently to digital challenges, and some Christian groups have already stepped up their online presence to regain visibility. Others emphasize local, face-to-face community work that doesn’t translate into viral metrics but sustains commitment in quieter ways. The interplay between loud online signals and steady offline institutions will determine whether the internet’s current patterns leave a lasting mark.

Ultimately, the MyCross findings force a simple recognition: digital attention and numerical majority are not the same thing, and both matter for the future of religious life. Being dominant online brings opportunities and risks, while being numerically larger brings social and institutional weight that shapes laws, education, and culture. Watching how these dynamics evolve will tell us whether online dominance becomes a leading indicator of long-term change or remains a distinct, separate phenomenon.