The Constitution has always been a living framework, but the amendments and the courts’ interpretations have steered how closely modern America follows the Founders’ original intent.

The Constitution was designed to set boundaries and to allow the nation to adapt without losing its core principles, especially limited government and individual liberty. Throughout U.S. history, amendments and judicial rulings have either tightened federal power or restored authority to the states. This tension between national reach and local control is at the heart of modern debates over what the Framers intended.

Many conservatives argue that the Founders wanted a durable charter that protected freedom by constraining central authority rather than expanding it. That view favors returning to original meanings where possible and resisting broad readings that create new federal powers. On issues from commerce to gun rights, Republicans tend to push for interpretations that limit federal overreach and preserve state sovereignty.

At the same time, the amendment process itself shows that change was expected and legitimate when required by the people and their representatives. Adding or refining amendments was built into the system, not banned by design, so long as the process followed constitutional rules. This balance allows the republic to correct mistakes while guarding against sudden shifts imposed without broad consensus.

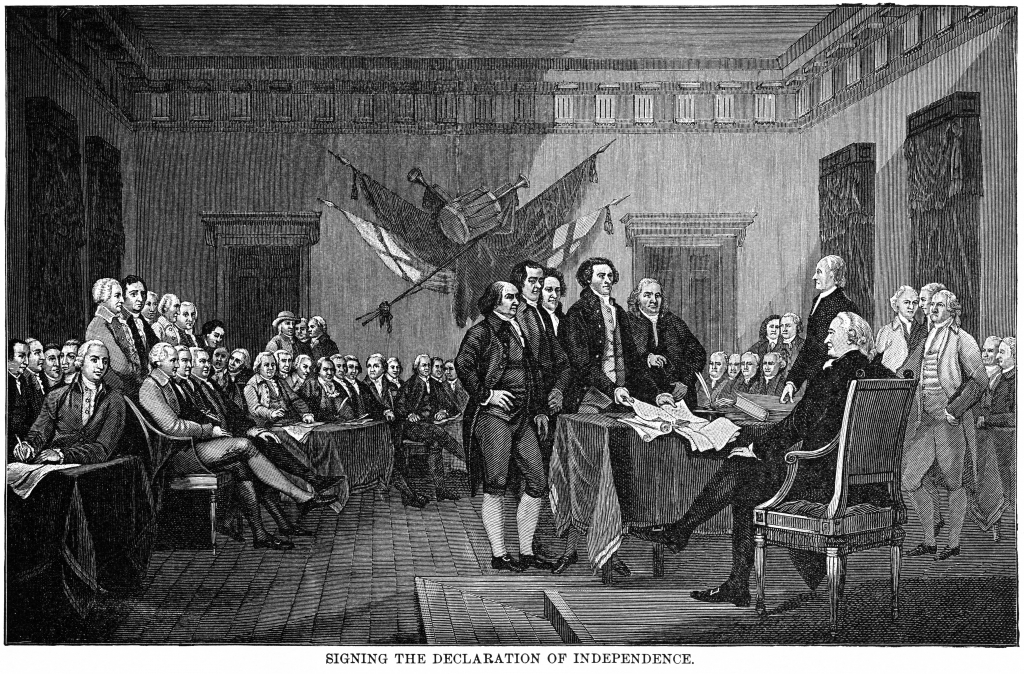

Originalists point to the Framers’ debates as guideposts for interpretation and for judging later changes to the charter. Virginia’s delegate to the Constitutional Convention, Edmund Randolph, wrote on July 26, 1787: “In the draught (draft) of a fundamental constitution, two […]” That fragment reminds us that the text and the surrounding discourse matter for how authority should be exercised.

Key amendments have reshaped the relationship between citizens and the state without discarding foundational aims. The Bill of Rights restrained national power and safeguarded individual liberties, and later amendments addressed voting and equal protection while expanding who participates in the civic project. Conservatives can accept necessary expansions when they are faithful to the rule of law and do not create open-ended federal mandates.

The 14th Amendment has proved particularly transformative, giving the courts a vehicle to apply protections across the states, sometimes in ways the Framers did not foresee. Republicans often critique expansive readings that treat the amendment as a catch-all foundation for sweeping federal programs. From this perspective, careful textual and historical analysis helps curb judicial activism and return contentious policy choices to elected officials.

The commerce clause and the development of federal regulatory power show how constitutional interpretation matters for everyday life and markets. Over time, the clause has been used to justify a widening array of national laws, a trend conservatives view as drifting from the Framers’ plan of limited union responsibilities. Reining in broad commerce readings is a priority for those who want a leaner federal footprint and stronger state experimentation.

Second Amendment debates highlight the clash between a living Constitution approach and an originalist stance. Republicans frequently defend a robust, individual right to keep and bear arms as consistent with the Constitution’s intent to protect citizen self-defense and to check government coercion. Where the courts have moved to protect individual rights, conservatives regard those decisions as restorations of the Founders’ protective design.

Federalism remains a practical bulwark against concentrated power and a mechanism for policy diversity, letting states serve as laboratories for governance. When Washington expands its reach, political accountability can suffer and local preferences can get steamrolled. Republicans argue that preserving state authority ensures closer alignment between government actions and the people they affect.

The amendment process itself offers a remedy when broad consensus forms around change, but it is intentionally difficult to prevent faddish or factional rewrites. That friction protects core liberties while still permitting corrective action. For conservatives, this design respects both stability and democratic evolution without handing unchecked power to judges or bureaucrats.

Courts play a crucial role in deciding whether the Constitution is being interpreted or reinvented, and Republican thinkers press judges to respect history, text, and structure. When judges anchor decisions in the Constitution’s language and the Framers’ structure, they limit the political branches from unchecked expansion. That restraint helps maintain a system where law governs, not policy preferences of a given era.

Ultimately, debates over amendments and interpretation are not abstract academic fights; they shape taxation, education, speech, and defense. Conservatives emphasize that fidelity to original meaning, coupled with cautious amendment when necessary, best protects liberty and promotes a functioning republic. Returning to those principles is about preserving a system that empowers people rather than central power brokers.