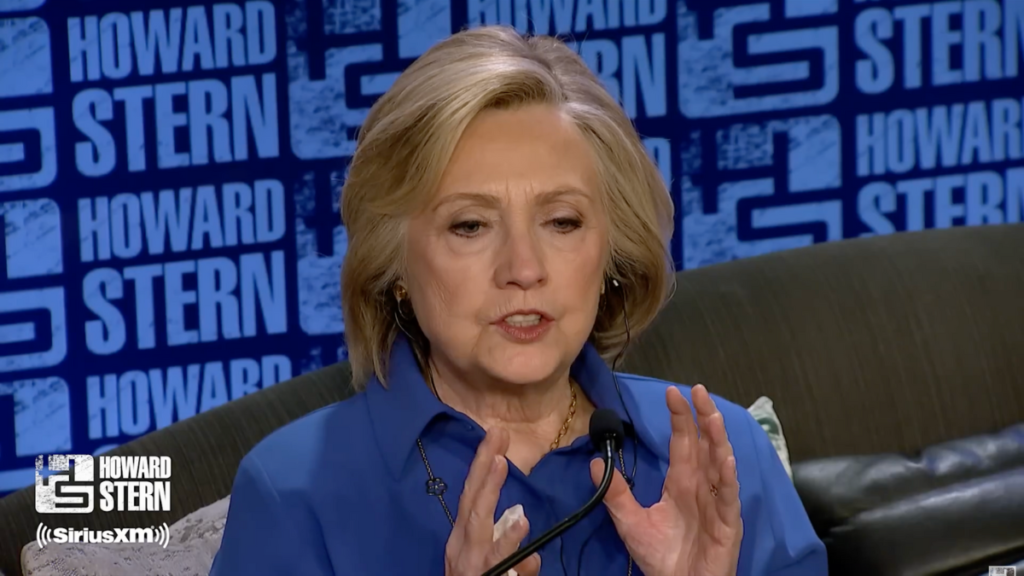

Hillary’s public voice often feels rehearsed and out of step, a sign of a broader problem where political elites talk more than they listen. This piece looks at how that pattern shows up in speeches, interactions, and public reactions, and why it matters for voters who value accountability and clear communication.

Hillary speaks, but she doesn’t listen. She half-absorbs events and the lives of other people, and coughs out a kind of instinctive Reader’s Digest annotated version, but mangles all the details as efficiently as bad AI. That blunt observation captures a recurring pattern: polished delivery over meaningful attention.

When public figures prioritize image over substance, the result is a gap between rhetoric and reality. Too often we see well-staged lines that echo talking points instead of concrete answers, and audiences walk away less informed. Voters deserve straightforward engagement, not rehearsed snapshots designed to sound empathetic.

Listening is more than nodding along during a speech. It means absorbing facts, acknowledging mistakes, and adapting policy when evidence demands it. In contrast, too many statements land as reflexive defenses or canned responses, which erode trust and invite skepticism about motives.

Accountability requires details and clarity, not clever phrasing meant to distract. When facts get compressed into tidy sound bites, the nuance disappears and with it any real chance for public scrutiny. That shorthand approach can make even legitimate points feel hollow and insincere.

The media amplifies this problem by rewarding charisma over substance. A sharp delivery or a viral moment can drown out persistent policy questions that matter to everyday Americans. Responsible coverage should demand specifics instead of treating every polished answer as a finished explanation.

Political experience is valuable, but it should not be a cover for evasiveness. Voters who respect competence also expect honesty about where things went wrong and what will be done differently. When leaders dodge specifics, the plausible explanation too often becomes self-preservation rather than public service.

There is a policy cost when listening is absent. Misunderstood or ignored local concerns produce one-size-fits-all solutions that fail in practice. Leaders who genuinely listen build policies that reflect real needs and practical tradeoffs rather than ideological abstractions.

Public institutions suffer when elites talk past ordinary people. Trust erodes and cynicism grows, which fuels polarization and disengagement. If the goal is to repair that trust, the first step is swapping polished monologues for real conversations that include pushback and follow-up.

Concrete examples matter more than clever lines. Citizens want to see how ideas translate into outcomes: budgets reconciled with priorities, timelines backed by measurable benchmarks, and accountability mechanisms that are enforceable. Without those elements, promises remain ornaments on a platform that people cannot rely on.

It is also worth noting how repetition dulls impact. Recycled phrases and predictable defenses create a sense that responses are manufactured, not earned. Authenticity shines through when leaders admit what they do not know and commit to finding out, rather than pretending to have all the answers.

Effective political communication is a two-way street: explain your plan and then listen to criticism so you can refine it. That iterative approach produces stronger policy and greater public confidence. When the loop is broken, decisions are made in an echo chamber and democracy is weakened.

Expectations should be higher for those who claim to represent the public. Clear, factual language and willingness to engage with inconvenient details are not optional. They are basic requirements if public service is to be more than image management.

The pattern of speaking without listening is not unique to any one person, but it is emblematic of a cultural problem among political elites. Restoring faith in governance starts with leaders who treat citizens as partners in problem solving, not as audiences to be impressed.