Why Brennan’s ‘Not Involved’ Claim on the Steele Dossier Falls Short

The public argument over the origins of the Steele dossier has been messy and partisan, but some facts are stubborn. As more documents and timelines emerged, it became harder to accept a neat, exculpatory narrative from intelligence officials who were central to the events.

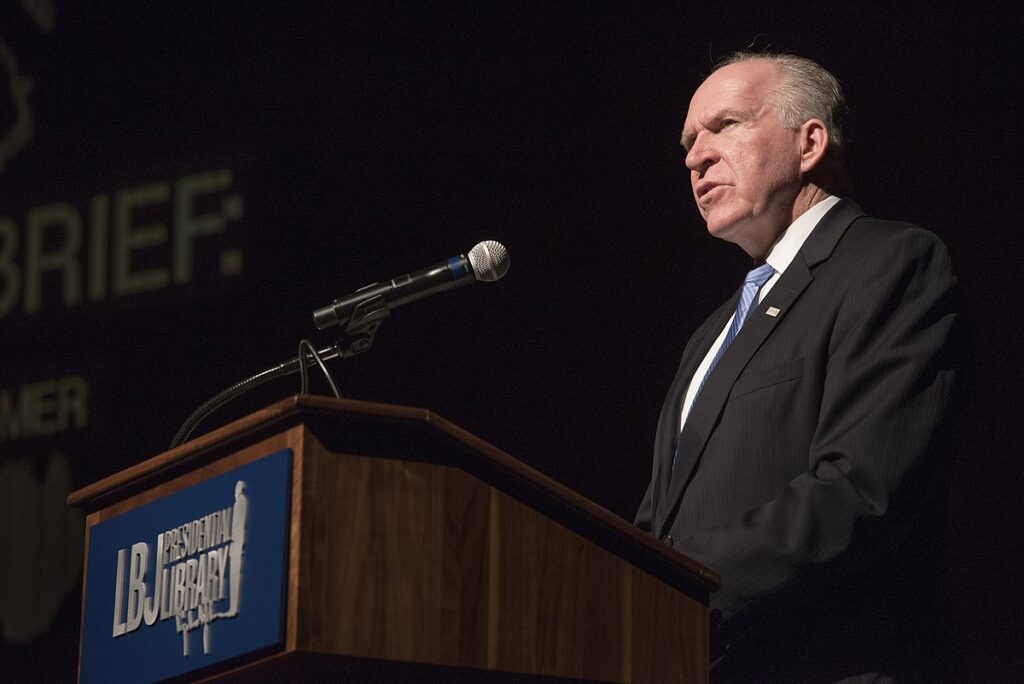

‘Brennan’s assertion that the CIA was not ‘involved at all’ with the Steele dossier cannot be reconciled with the facts.’

Officials like John Brennan defended the agency’s distance from the dossier, yet emails and memos show contacts and handoffs between private researchers, contractors, and intelligence analysts. That web of communication may not be a smoking gun by itself, but it undermines a rigid denial and raises questions about judgment and oversight.

A Republican perspective here is straightforward: agencies must be honest about their actions and accountable when their conduct risks political interference. When intelligence work touches an election and a political opponent, transparency is not optional, it is essential to preserve public trust and the integrity of future operations.

The timeline matters. The dossier’s compilation, funding channels, and the way it circulated among journalists, law enforcement, and intelligence figures created a pathway where private opposition research and official scrutiny became entangled. That entanglement is exactly what critics warned about and what conservatives point to when calling for reforms.

There were also procedural consequences to consider, like the use of information in applications to surveillance courts and the reliance on human sources with potential bias. Those steps exposed a system that treated raw, unvetted material as enough to move forward, which should make any reasonable observer uneasy about institutional safeguards.

Accountability does not mean politics for the sake of politics, it means fixing the gaps that let political narratives warp intelligence judgment. From a policy view, this argues for clearer walls between investigative courts, intelligence collection, and politically motivated research so that evidence standards are restored and protected.

Republicans who scrutinize this episode are not simply playing opposition, they are pointing to lasting reforms that would tighten reporting standards and improve oversight of how outside material is vetted. Better recordkeeping, stricter attestations about source credibility, and congressional review can help prevent future confusion and abuse.

The public also deserves plain answers about who knew what, when, and why certain decisions were made in real time. That is why conservative requests for declassification, timelines, and sworn testimony are framed as necessary steps to rebuild trust and ensure similar mistakes do not recur.

At the end of the day, insisting the CIA had no involvement is not enough, and sticking with that claim in the face of documentary evidence leaves the public with more questions than answers. If intelligence agencies want to earn back confidence, they will need to stop defending convenience and start embracing clarity.